Living on the Edge: A Tour of Bay Habitats

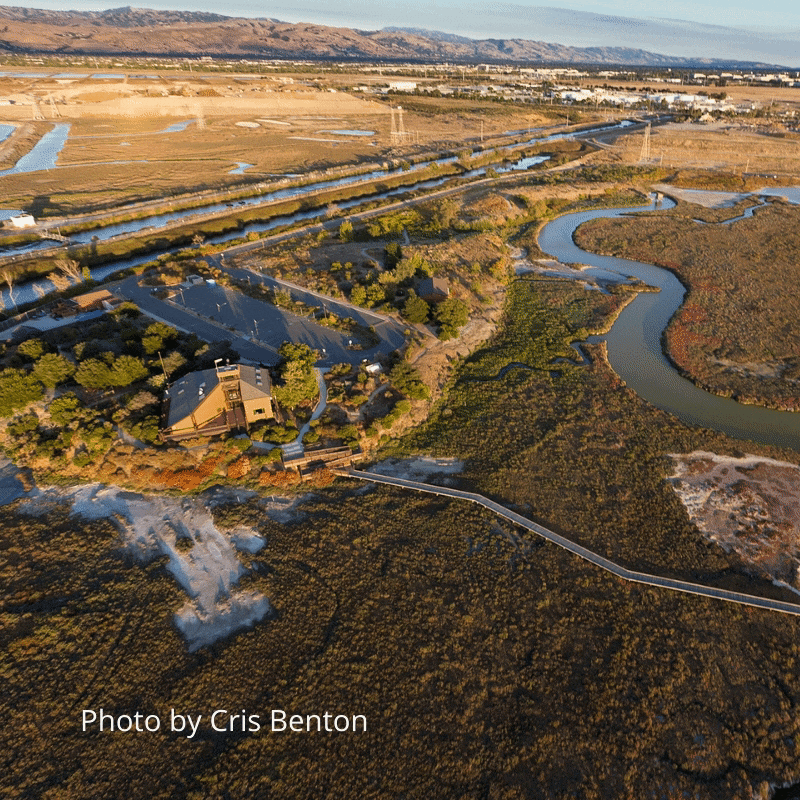

As you ride your bike or take a hike around the habitats at the Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge, stop along the way to learn more about the history of the site, the plants and wildlife that live here, and the restoration work being done to ensure a resilient future for our community.

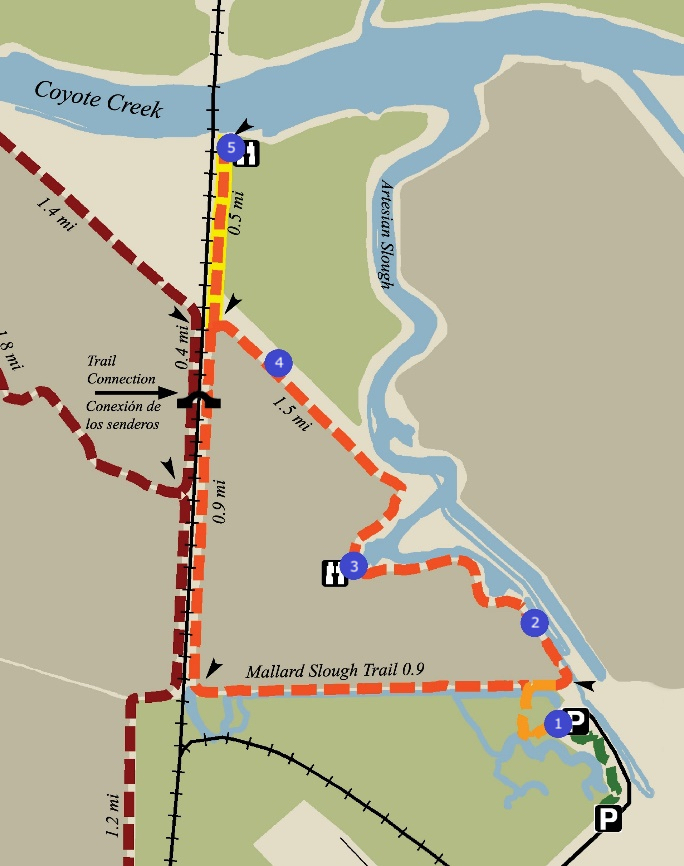

At each stop location (see map below), you will find a sign with a QR code. Scan the code with your mobile device’s camera or app. This will open a web page with information, photos, and additional links about four different topics relevant to each stop.

If you are unable to visit the Refuge in-person, please click the links below to visit each stop virtually!

We hope you enjoy this self-guided tour at the Refuge. Come back and visit, as topics may change throughout the year! Also be on the lookout for more tour locations coming soon!

This program is brought to you by a grant through California Coastal Commission’s Whale Tail License Plate program and through a partnership of many local organizations: Keep Coyote Creek Beautiful, San Francisco Bay Wildlife Society, San Francisco Bay Bird Observatory, and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

History of Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge

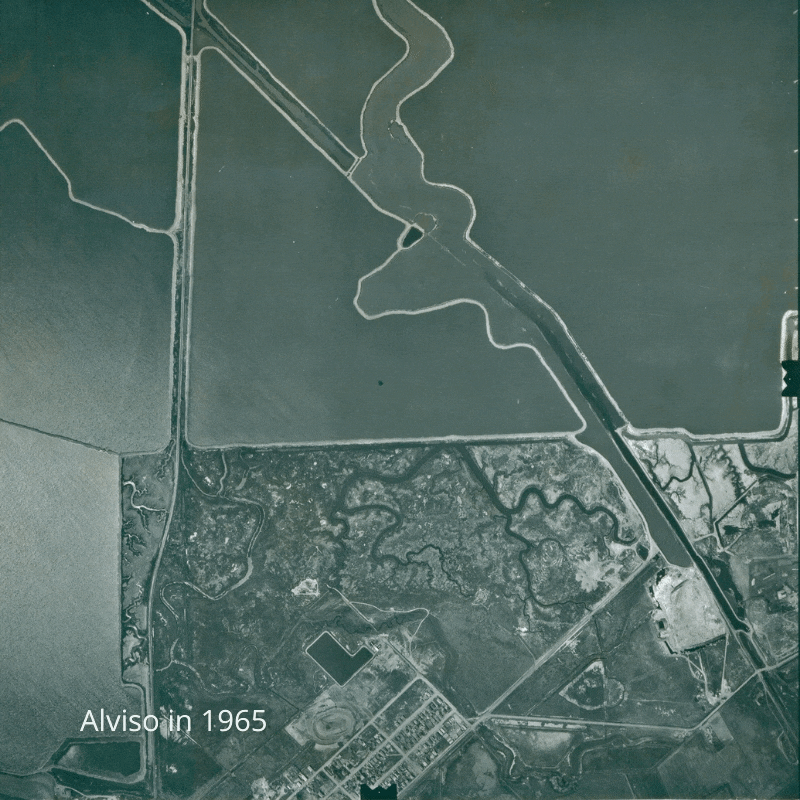

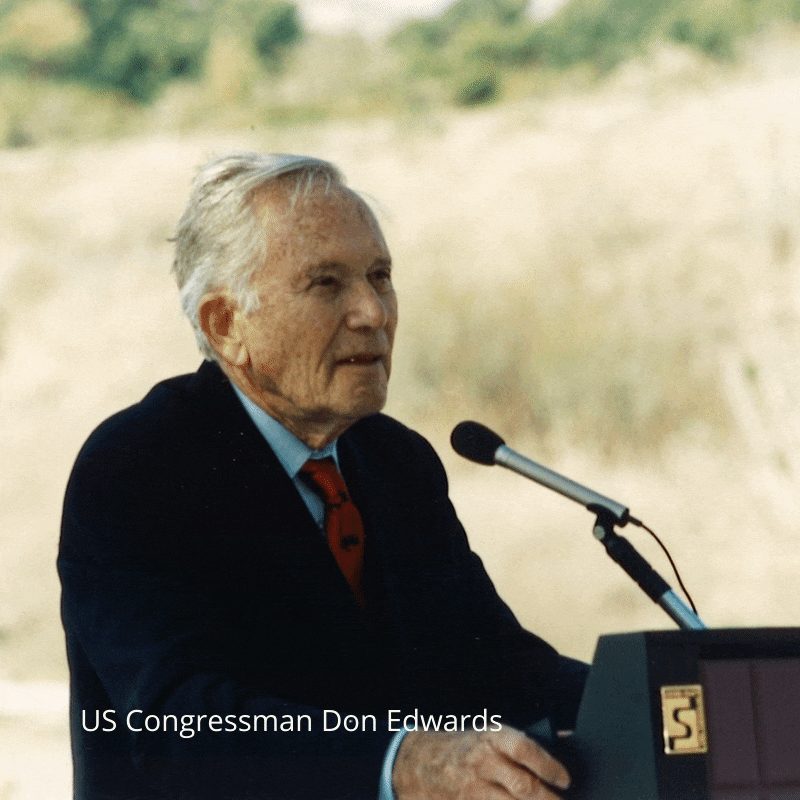

Through the early 1900s and into the 1960s portions of the San Francisco Bay and surrounding baylands had become a waste land – raw sewage, garbage, and landfill filled the edges of the bay. This alarmed many residents that recreated on the Bay, and enjoyed the windy edge of the Bay and all the plants and animals that live here. A group of residents formed a group called the South San Francisco Baylands Planning, Conservation and National Wildlife Refuge Committee, and they lobbied Congressman Don Edwards to create a National Wildlife Refuge in the South Bay. In 1972, Congress passed HR 111, sponsored by the Bay Area Delegation. The San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge was authorized to be 23,000 acres. The Refuge was formed, and land could be acquired. The Refuge has grown over the years and in 1988 was authorized to acquire land for a total size of 43,000 acres. The Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge was born out of the hard work and dedication of residents in the South San Francisco Bay. The organization, now called, the Citizens Committee to Complete the Refuge is still active today, they are dedicated to ensuring current and future generations of Bay Area residents have a clean, healthy, sustainable and vibrant San Francisco Bay.

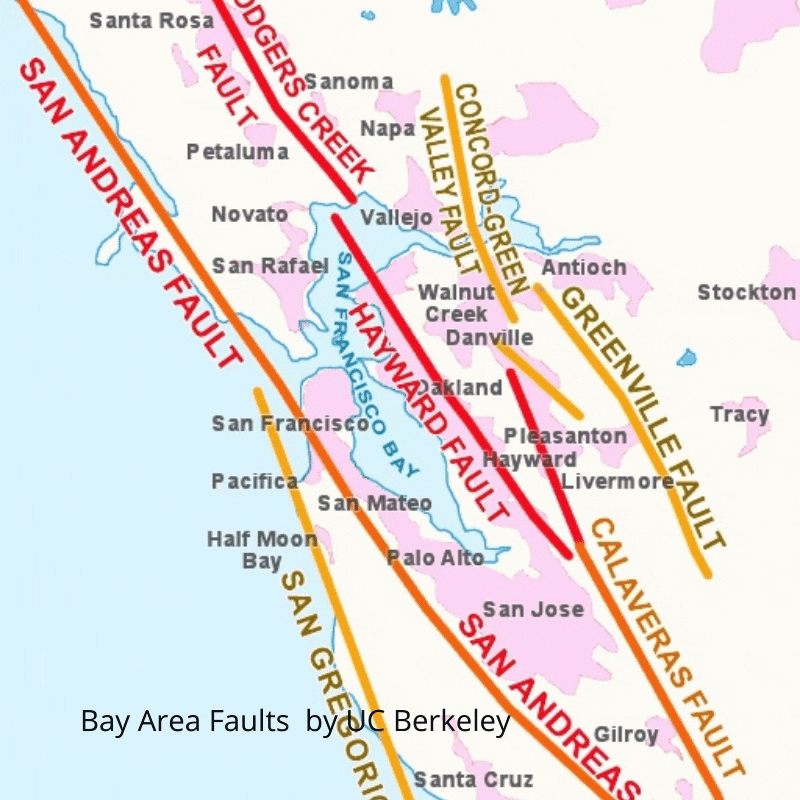

Regional Geology

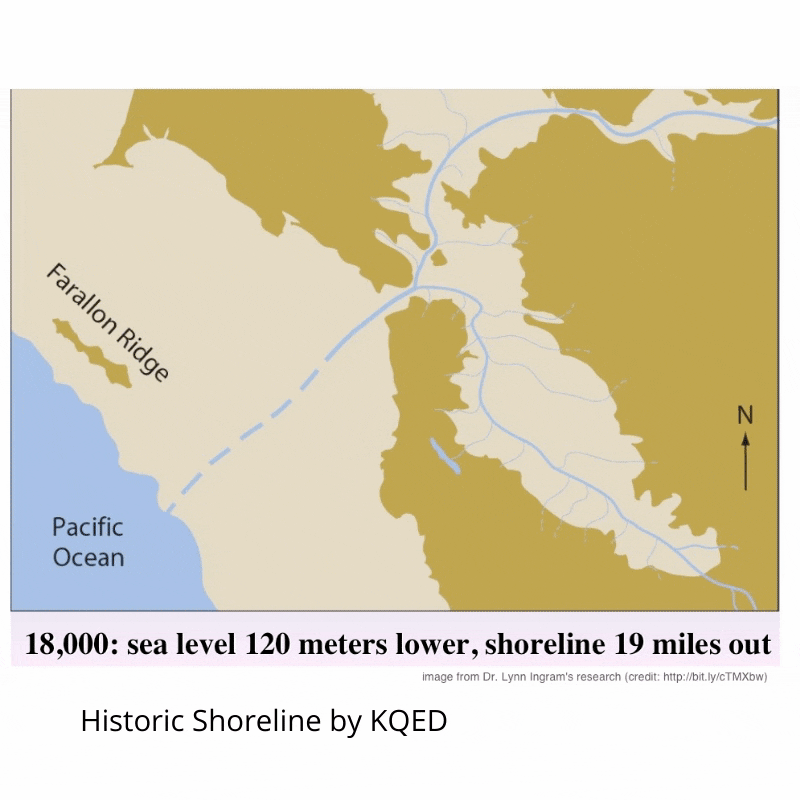

The story of the San Francisco Bay begins millions of years ago when active faults folded and lifted the Santa Cruz Mountains and Berkeley Hills. During the last Ice Age (20,000 years ago,) mammoths and saber-toothed cats roamed the broad river valley between the Coastal Ranges. As temperatures warmed, the great glaciers melted and sea levels began to rise. Over many generations, the first human inhabitants witnessed the rising ocean waters enter through the Golden Gate and eventually fill this ancient river valley. Today, we call this body of water the San Francisco Bay.

Native Plants

With the help of many volunteers and staff members over the years, the Native Plant Garden at the Environmental Education Center flourishes with various California native plants that provide food and shelter for much wildlife. Some of the native plants in the garden include: Black Sage, California buckeye, California Fuschia, Lemonade Berry, Toyon, and Yarrow just to name a few. Visiting the Native Plant Garden you will hear songbirds singing, you’ll see butterflies and bees enjoying the nectar of flowering plants, and you may spot jackrabbits hopping among the foliage. The Native Plant Garden is also a Monarch Waystation, providing Monarch butterflies a place to rest, feed, and lay eggs along their long migrations.

Gray Foxes

Gray Foxes are small omnivorous mammals that live on the Refuge. They eat plants and berries, but also enjoy rabbits and mice! They are specially adapted to climb trees, with rotating wrists and semi-retractable claws! Kits are born in mid-late Spring, and stay with the family through the end of Fall.

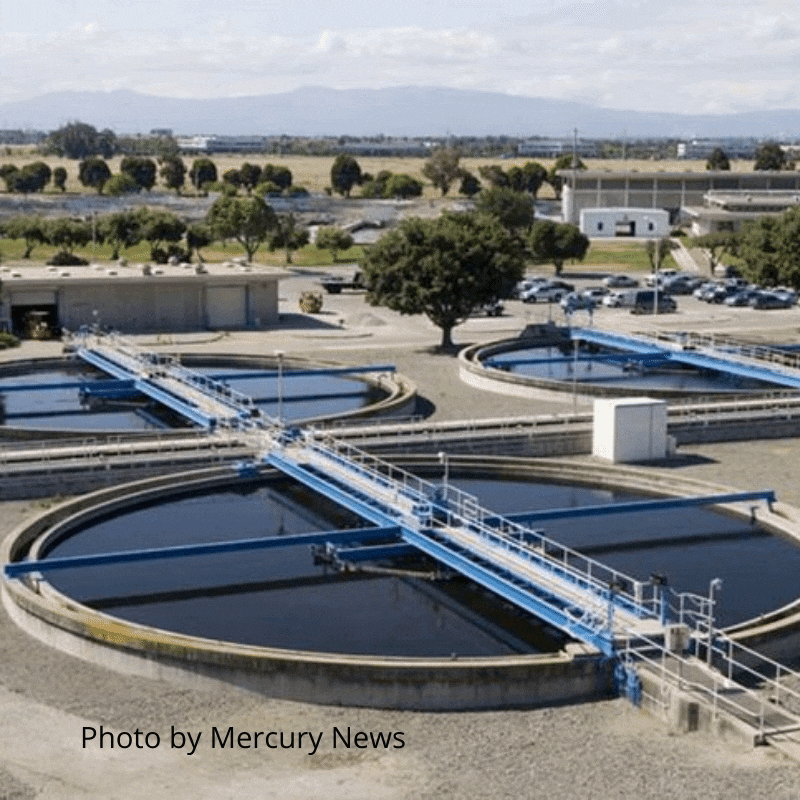

San Jose-Santa Clara Regional Wastewater Facility

The San José-Santa Clara Regional Wastewater Facility is the largest advanced wastewater treatment facility in the western United States. Starting as a small sewage plant in the 1880s, it now serves 1.4 million residents. The facility’s wastewater is treated to very high national standards, protecting public health and environment. Water from the facility exits through Artesian Slough.

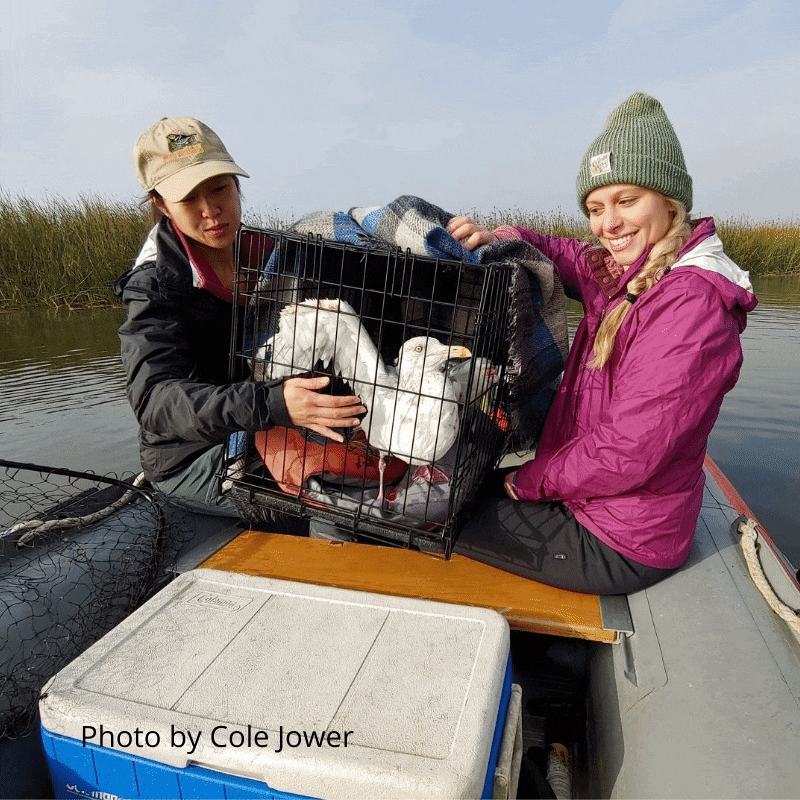

Avian Disease Prevention

The San Francisco Bay Bird Observatory (SFBBO) conducts surveys in the South Bay every year as part of the Avian Disease Prevention Program. Scientists and volunteers survey Coyote Creek (also known as Artesian Slough) and Guadalupe slough here in the refuge in search of sick, injured or dead birds, which are removed from the waters to prevent the spread of avian botulism.

Avian botulism is a disease found in birds caused by a toxin released by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum. This disease can affect waterfowl such as ducks and geese as well as waterbirds such as cormorants and gulls. The bacterium prefers warm, anaerobic, protein-rich environments, which make dead birds a good host of the disease, especially during warmer months. Maggots can also be carriers of the disease, and as birds consume maggots, the disease can spread rapidly. Birds infected with botulism experience a gradual paralysis where they have difficulty diving, flying, and keeping their head up, and as a result, they often die of starvation or drowning. By removing these sick and dead birds, SFBBO helps reduce the chances of an outbreak and promotes healthy waterbird populations!

Urban Runoff Pollution

Living in an urban landscape and surrounded by 5+ landfills, wildlife at the Refuge is threatened by trash, microtrash and urban runoff. Urban runoff is the result of rainwater transporting trash and pollutants through cities and neighborhoods into waterways and natural environments. One of the best ways to protect wildlife at the Refuge is to dispose of trash properly and prevent pollutants from entering storm drains.

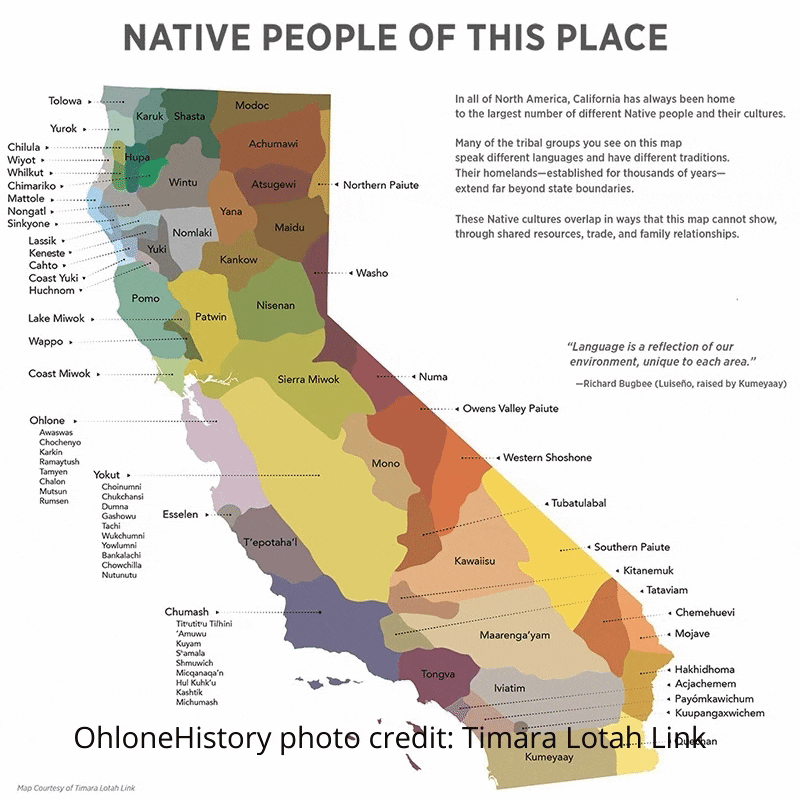

Ohlone History

Ohlone (Oh-lone-e) Indians refers to the collective indigenous tribes that have lived in the San Francisco Bay Area for thousands of years. Ohlones used the waterways in this area to collect and hunt an abundance of resources such as fish, mussels, waterfowl and a variety of plant species. The Ohlones that occupied this area created boats, homes, mats, clothing, and tools from the common tule plant which lines the edges of the tidal slough.

Bird Migration

Many birds are migratory, meaning they travel long distances between the places they breed and the places they spend the winter. As the weather gets warmer in the spring, migratory birds typically travel north to take advantage of burgeoning food resources, especially insects. As the weather gets cooler in the fall, migratory birds travel to warmer areas where more food is available in the winter months.

The Don Edwards National Wildlife Refuge lies within the Pacific Flyway, a major migratory route for birds. Along this migratory route, some birds may travel thousands of miles to places as far away as Alaska or South America. Such a long journey requires a lot of energy! Because the refuge provides abundant food for birds, many species stop here during spring and fall migration to rest and feed before continuing on their epic journeys.

Some migratory birds that spend the winter here include several duck species, such as the Bufflehead, Canvasback, and Red-breasted Merganser, as well as grebes, including the Eared, Western, and Clark’s Grebe. Take a close look at nearby vegetation or on the ground and you may see and hear smaller migratory birds, such as White-crowned Sparrows, Golden-crowned Sparrows, and Yellow-rumped Warblers.

If you’re visiting in the summer, other migratory birds you may find include Barn Swallows and Cliff Swallows zooming through the sky catching insects. If you’re lucky, you may also see shorebirds spinning in circles in the water. These birds are called phalaropes, and their peculiar spinning behavior forces water away from the surface, causing an upward flow of water from below with a bounty of food!

Year-round Birds

The Don Edwards National Wildlife Refuge is a hotspot for birds year-round, providing ideal habitat and plenty of food. Gazing over the salt ponds and mudflats, you may see shorebirds such as American Avocets and Black-necked Stilts roosting or feeding. Mallards, Gadwalls, Canada Geese, and American Coots are common sights floating on the water or resting near the water’s edge. Large wading birds, including the Great Blue Heron, Great Egret, and Snowy Egret can also be found here throughout the year using their spear-like bills to catch fish and other prey. Scanning the marsh, you may even catch a glimpse of a hawk, such as the Red-tailed Hawk and Northern Harrier. Among the vegetation, listen for the buzzy trills of songbirds that call the refuge home all year long, including the Savannah Sparrow, Marsh Wren, and Red-winged Blackbird. Look up at the sky and you may notice Turkey Vultures soaring overhead or California Gulls flocking and calling. No matter where or when you visit the refuge, you’re bound to see some wildlife nearby!

Breeding Birds & Decoys

Because the Don Edwards National Wildlife Refuge provides great habitat for birds, many species breed here every year. You may find Pied-billed Grebes sitting on nests in shallow water, or Black-necked Stilts and American Avocets nesting on the ground near the water. Many other species also breed in the refuge, from tiny Anna’s Hummingbirds and Savannah Sparrows to awe-inspiring White-tailed Kites and Peregrine Falcons.

As you scan the ponds, you may notice islands with what appear to be birds sitting very still on them. These human-made islands were constructed in former salt ponds to help attract birds and provide nesting habitat for them. The statuesque birds you see may in fact be decoys! These tern decoys and a colony call playback system were placed on the islands to help attract Forster’s Terns (Sterna forsteri), a species that was once one of the most numerous colonial-breeding waterbirds in South San Francisco Bay, but whose numbers have declined in recent years. In 2019, with the help of the decoys and nesting islands, Forster’s Terns re-established a breeding colony in the pond for the first time in 8 years!

Food Chain

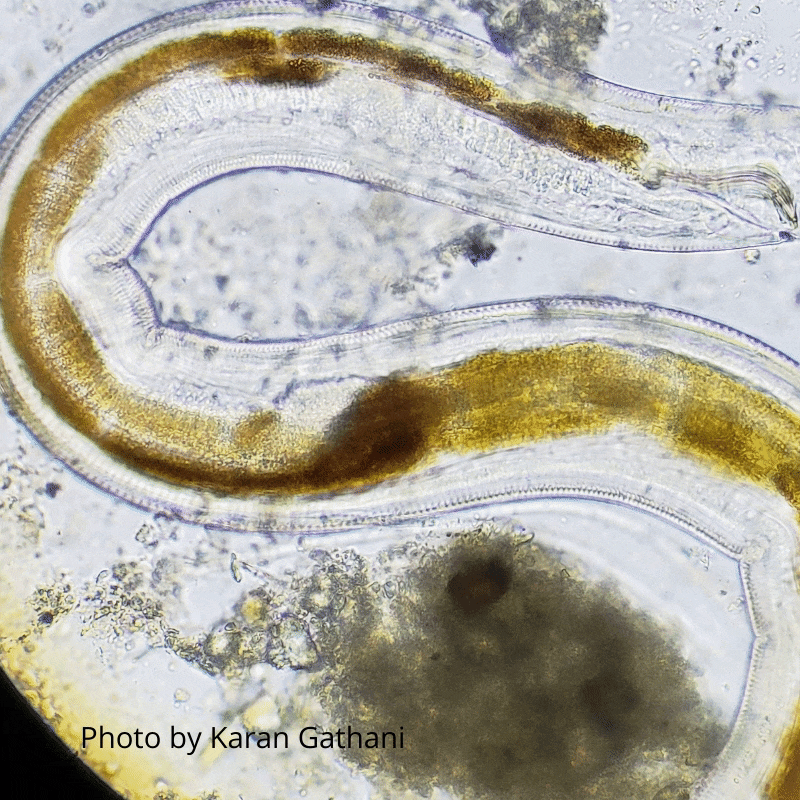

If you take a closer look at the marsh water, you’ll find countless small critters called zooplankton that swim around and eat microscopic plants called phytoplankton. These small plants and critters, some that cannot be seen with the naked eye, are the foundation of the food chain of the non-tidal slough habitat. A food chain is a sequence that shows the organisms that feed on each other. For example, phytoplankton is eaten by zooplankton, zooplankton is eaten by small fish, small fish are eaten by larger fish, and larger fish are eaten by birds. Within the non-tidal slough ecosystem that are many food chains. Pollutants such as pesticides that enter the Refuge through urban runoff threaten the health and balance of the non-tidal slough food chain.

Function of the Fish Gate

The fish gate was built to prevent fish, mostly chinook salmon and steelhead trout that are threatened or endangered, from being trapped in the shallow salt pond. The salt pond cannot support fully grown salmonids because there is not enough oxygen in the shallow water that modulates with the tide. However, you can often see birds by the fish gate waiting to capture any small fish that manage to make it through the gate, such as this great egret. To reduce entrapment, the fish gate is closed during the outmigration season of juvenile steelhead.

Salt Pond Restoration

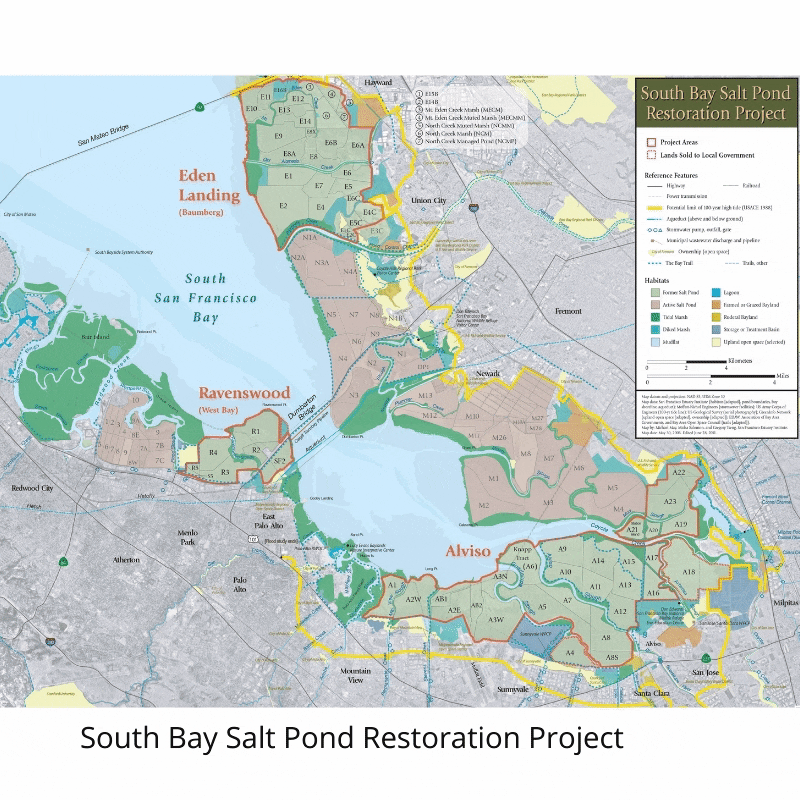

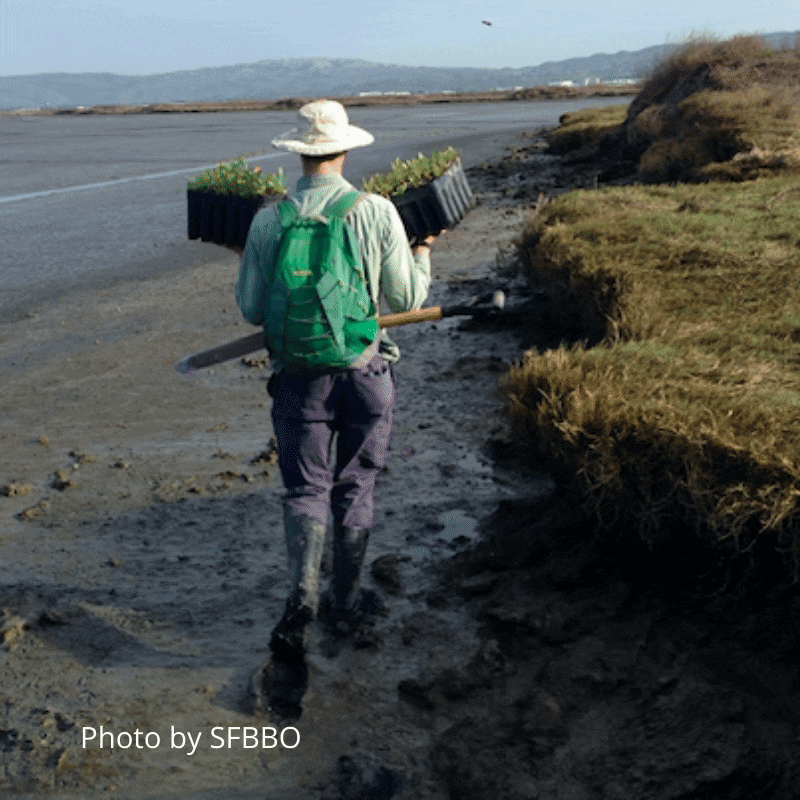

The Don Edwards National Wildlife Refuge is involved with the largest tidal wetland restoration on the West Coast called the South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project. This project will convert 15,100 acres of former industrial salt ponds to a mix of tidal marsh, mudflat, managed pond, open water, and other wetland habitats. Restoration of the salt ponds requires recovery of the tidal flow by removing the mud walls or levees that impede the entrance of water to the ponds. Through time, weed management and native plant propagation through the San Francisco Bay Bird Observatory nursery with over 2600 native Bay Area plants must be done in order to generate a vegetation structure within the salt marsh. Plants include Alkali heath (Frankenia salina), Pacific aster (Symphyotrichum chilense), and Salt marsh baccharis (Baccharis glutinosa).

These salt marshes have organisms adapted to the salinity and floods of this type of ecosystem. One is pickleweed (Salicornia pacifica), a halophytic and succulent native plant that dominates the lower marsh. Pickleweed gives habitat and resources to several residents of the marsh, including the endangered Salt Marsh Harvest Mouse (Reithrodontomys raviventris). Because pickleweed is a halophyte, it tolerates high concentrations of salt, which is filtered out through the roots. Unlike many other plants, pickleweed can store excess salt in the vacuoles (storage organelles) of the cells at the tips of the plant. This gives the pickleweed a salty taste!

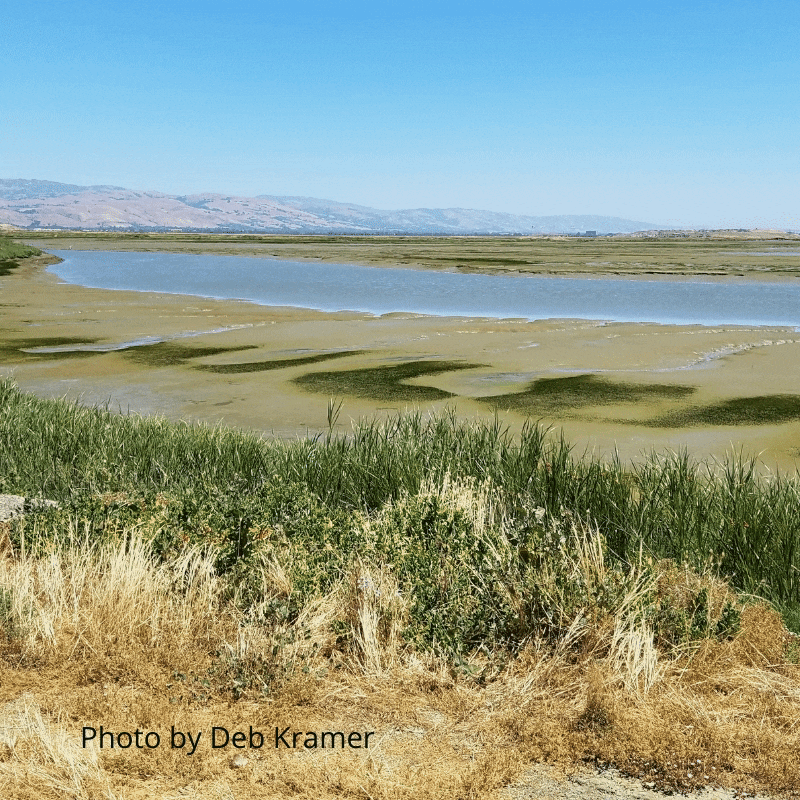

Mudflat Habitat

Tidal mudflats are intertidal areas covered twice a day by the Bay’s high tides and are exposed during low tides. Mudflats support an abundance of life with an estimated 40,000 organisms living in two handfuls of mud – most of the organisms are microscopic. Examples of life in the mudflats include shellfish, snails and other invertebrates, as well as algae and eelgrass. Shore birds visit the mudflats to eat the larger and more visible creatures that live there such as snails, mussels, worms, and clams.

Fish in the South Bay

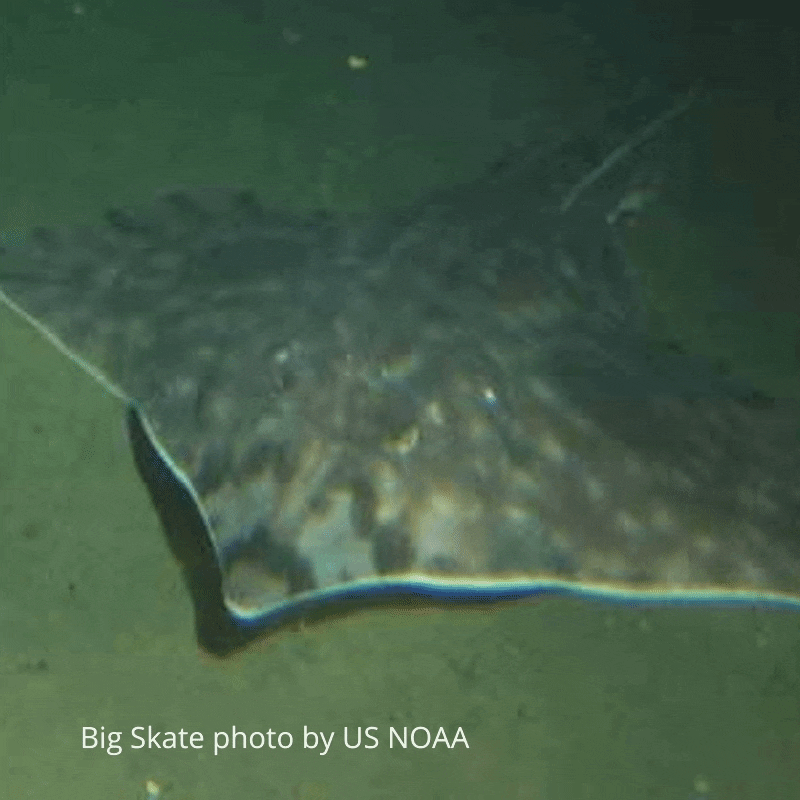

Looking into this gray, murky water you may wonder – are there any fish in there?! The answer is YES! There are! Scientists have found many species of fish throughout the lower reaches of the South Bay. Topsmelt, three-spined sticklebacks, long-jawed mudsuckers, northern anchovies, and bat rays! Various species of shrimp abound in the Bay and sloughs. Occasionally, when the salinity of the water is high comb jelly’s follow the tides and drift into the South Bay. Additionally, eleven species of sharks can be found in the San Francisco Bay. The most common is the Leopard Shark. The sharks feed on crustaceans, mollusks, and small fish found on the bottom of the bay. The Bay’s water ebb and flow, the fish, shrimp and sharks come and go on the tides. Look closely, you may see a shadowy figure under the depths or better yet, watch the birds, and the seals as they catch their prey. You never know what species they may find!

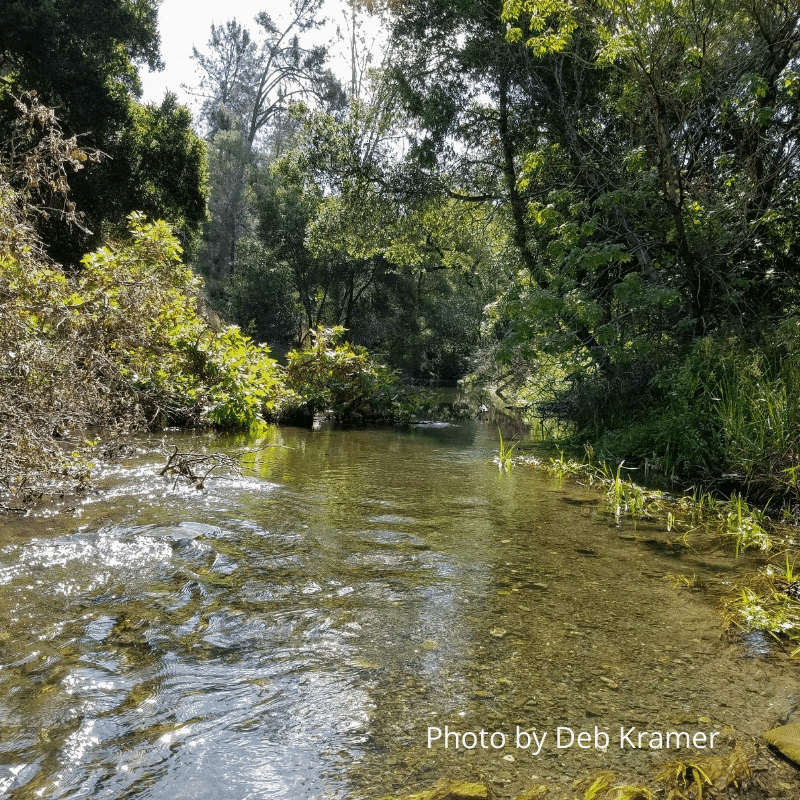

Coyote Creek Watershed

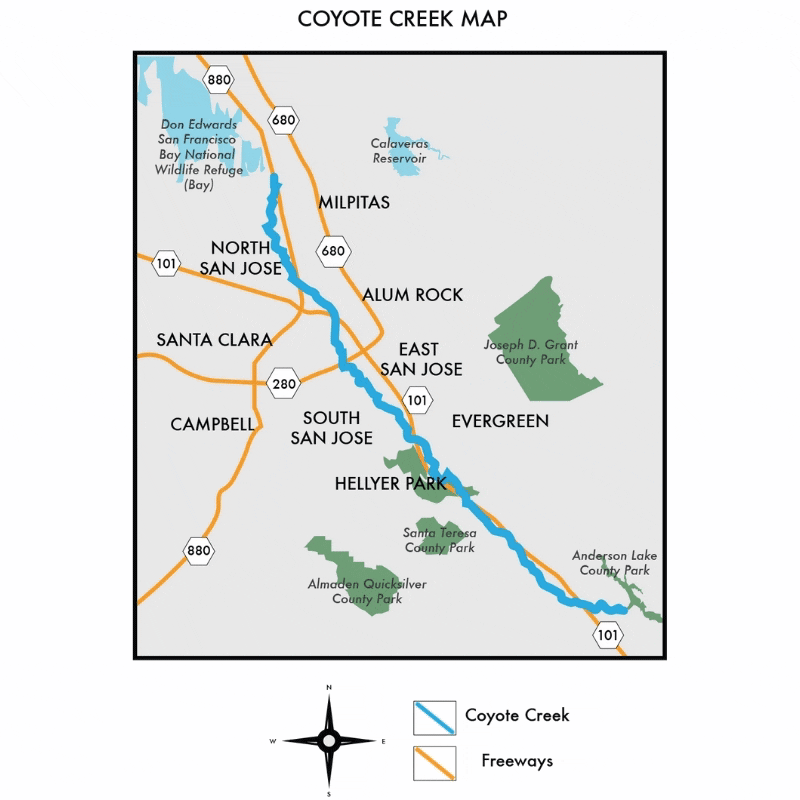

With headwaters starting deep within Henry Coe State Park near Morgan Hill, Coyote Creek travels 64 miles north through San Jose and ends in the south San Francisco Bay. The fresh water from Coyote Creek helps balance the nearby saline ecosystems thus allowing a wider variety of plants and wildlife to flourish. As the largest watershed in Santa Clara County, Coyote Creek faces many issues such as urbanization, trash, pollution and alteration. Do your part and help protect this wonderful ecosystem.

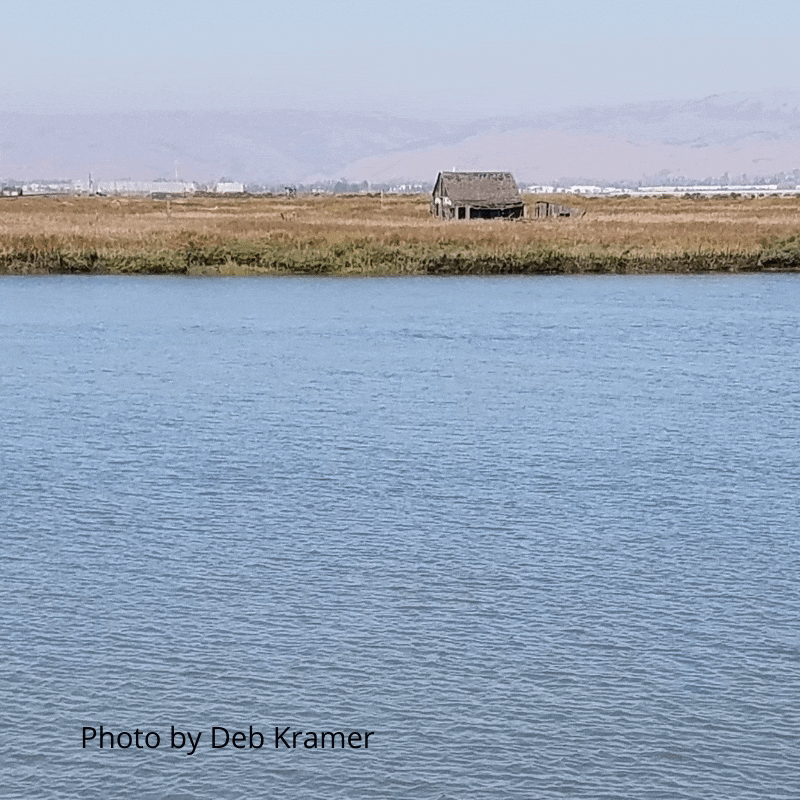

Drawbridge: Our local ghost town

Drawbridge, the ghost town of the South Bay, once florished as a paradise for duck hunters and adventure seekers alike. Originally occupied by a sole bridge attendant in 1876, by 1926 Drawbridge would eventually grow to have 80 to 90 homes, two hotels, boat builders and many gun clubs. As the landscape became polluted by sewage and chemicals from the nearby canneries, residents began to abandon their former homes. The last resident, Charlie Luce, moved out of Drawbridge in 1979.

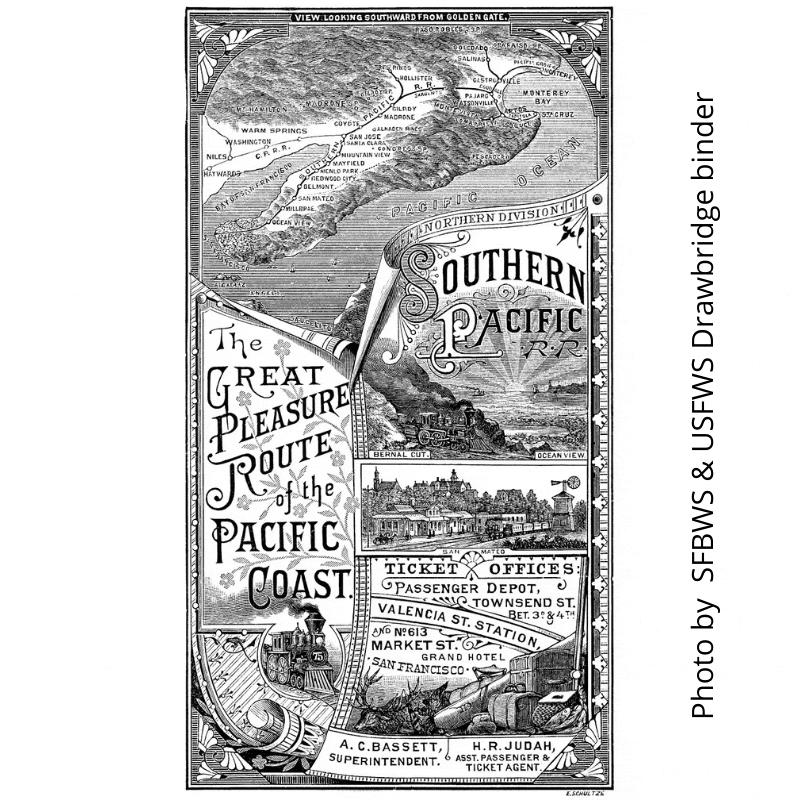

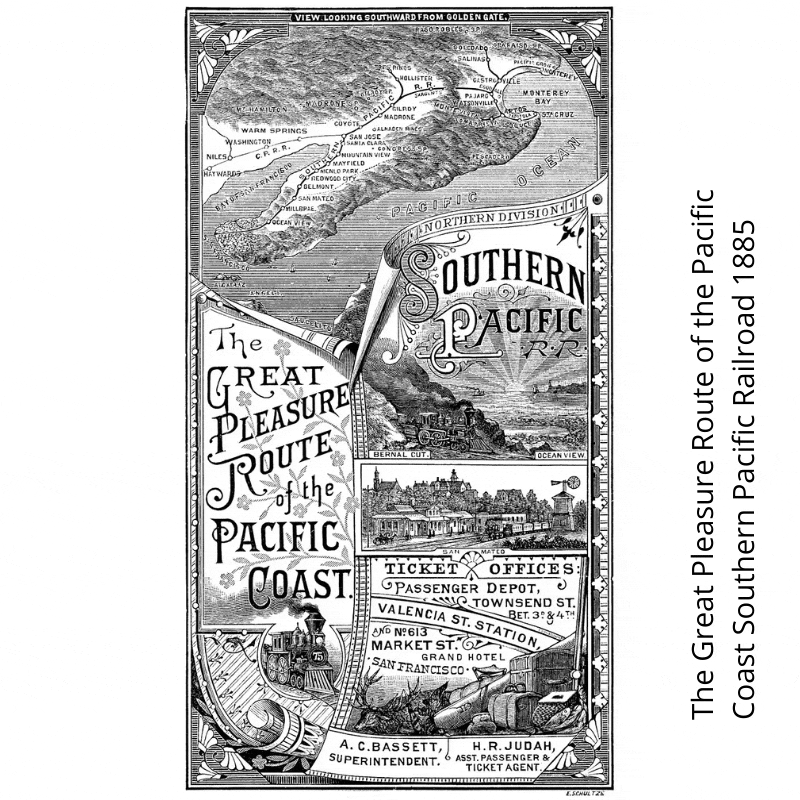

Southern Pacific Coast Railroad

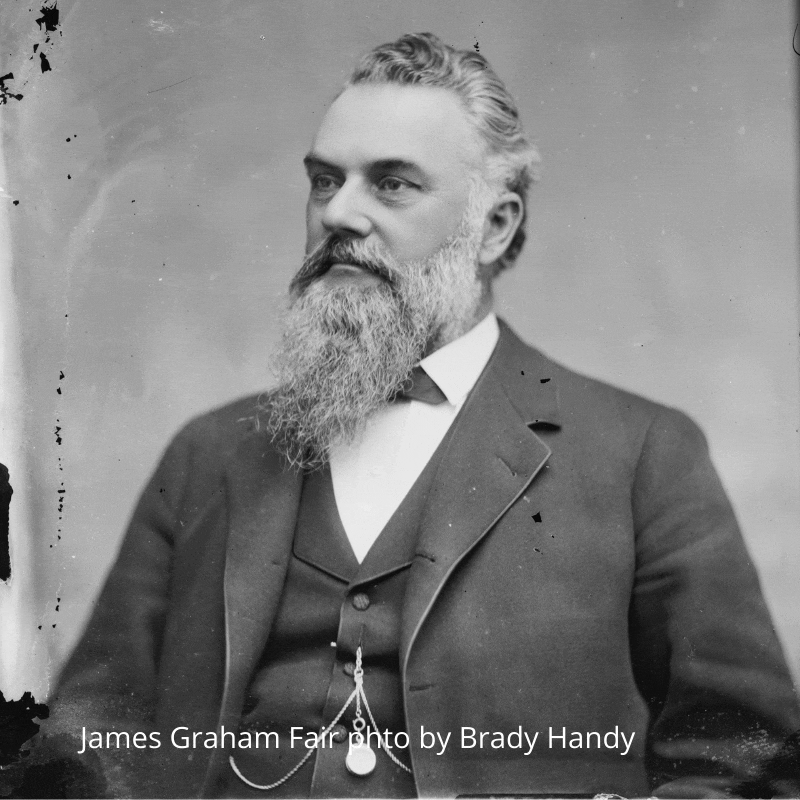

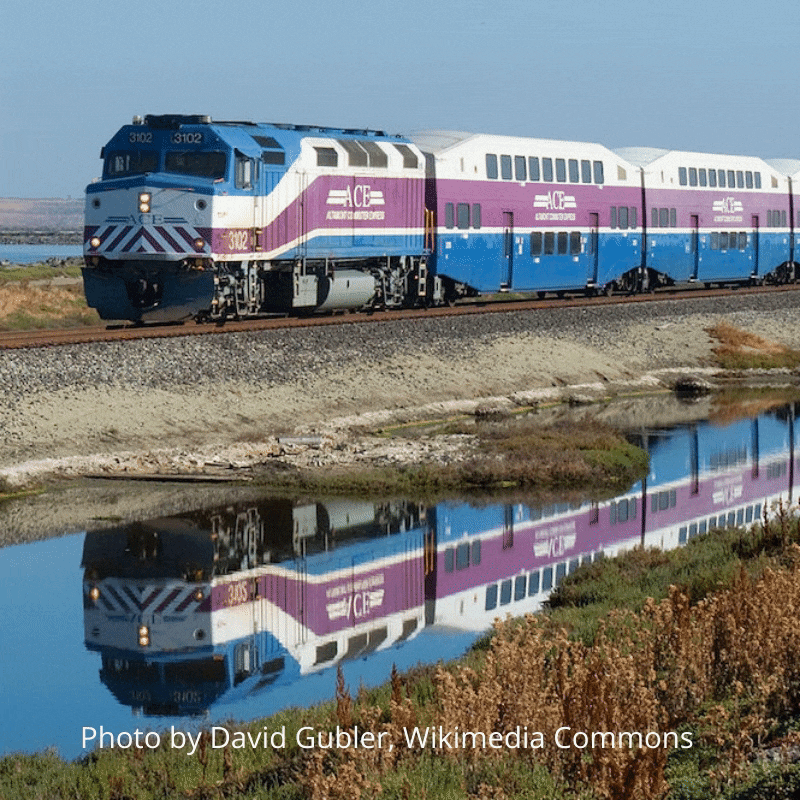

The narrow-gauge South Pacific Coast Railroad began its operation in May 15, 1880. Built by Comstock millionaire James Fair and Alfred “Hog” Davis, the rail line ran from Alameda to Santa Cruz. James Fair was an Irish immigrant, he grew up in Illinois and then moved West. He worked many gold mines, and silver mines. He ultimately invested in the Comstock Mining District in Virginia City, Nevada where he made his millions. Alfred “Hog” Davis, a banker, was his partner and front man. Over 600 Chinese immigrants worked to lay the track, built the two over 5,000 foot tunnels. The work was dangerous and sadly, 31 workers died building the railroad line. The narrow gauge was best for the winding tracks that led up into the Santa Cruz mountains. The train transported passengers and freight. Freight included redwood lumber from the Santa Cruz Mountains and fruit from the Santa Clara Valley. Much of the line was decommissioned in the 1930’s. However today, the portion that goes through the marshes of the Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge is managed by Union Pacific, and is used by Altamont Commuter Express (ACE), Amtrak, and many freight trains. This single track is one of the busiest tracks in Northern California!

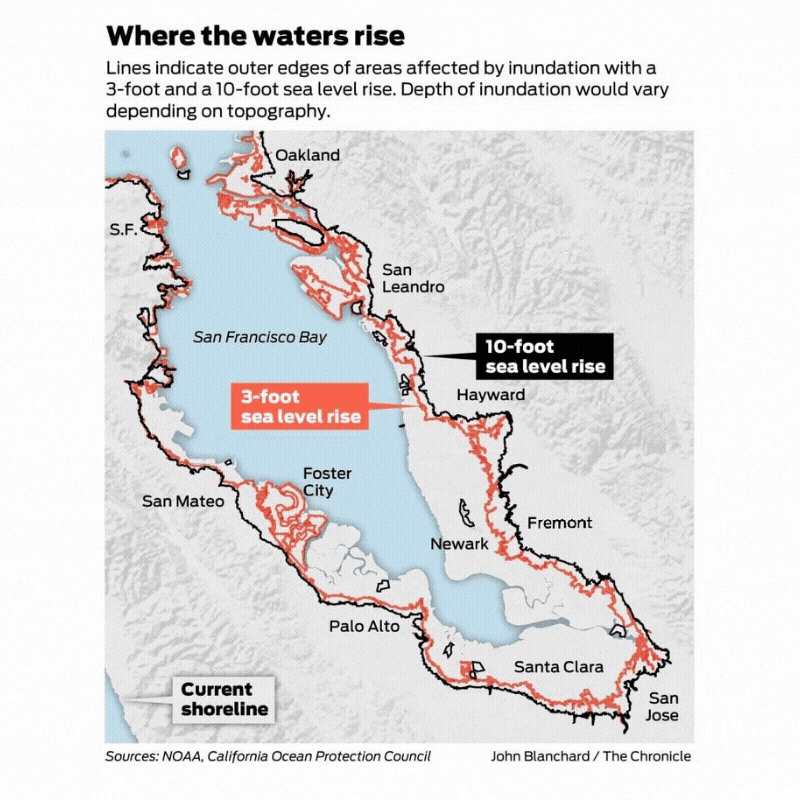

Sea Level Rise

Sea level rise is a result of anthropogenic global warming which causes ice caps to melt and water levels to increase along coastal regions. As water rises, it will change the landscape and force plants and animals to adapt quickly to a changing environment. Tidal wetlands are a natural buffer against flooding since they are capable of absorbing much of the extra water like a sponge and releasing it back to the Bay at a slower rate. Also, the marsh plants and soil sequester carbon dioxide in the air.